Narcissism and Competitive Communication in Individualistic Cultures

"When the healthy pursuit of self-interest and self-realization turns into self-absorption, other people can lose their intrinsic value in our eyes and become mere means to the fulfilment of our needs and desires."

- P.M. Forni, The Civility Solution: What to Do When People Are Rude-

***

Conversational Narcissism, described by sociologist Charles Derber as "the key manifestation of attention-getting psychology in America", occurs when someone craves and competes for attention (according to Dr. Derber’s point of view, attention is some sort of social currency regulated by power dynamics: the more "important” someone is, the more attention they’ll expect to receive. For an overview of the impact power dynamics have on non-verbal communication, see post "Expressions of Power and Status in Non-Verbal Communication”).

Conversations can be either cooperative or competitive: good conversations imply that participants are willing to both take and give attention, while competitive conversations aim at channelling attention in one direction only, task usually achieved through the tactics of conversational narcissism.

The difference between the two lies in the type of response we choose, shift- v support-response.

The shift response:

- We pretend to have a "socially acceptable" interest in what we hear while we wait for the occasion to bring the conversation back to us. We don't listen to understand and empathize, we listen to respond;

- We use a lot of filler-words ("Mmmh", "Really?", "Interesting") or non-committal support responses ("That's terrible", "You should do it") to convey a false sense of engagement;

- We offer reassurance: "I know how you feel". By doing so, we deprive the other person of a chance to share their concerns. Instead, we talk about ours;

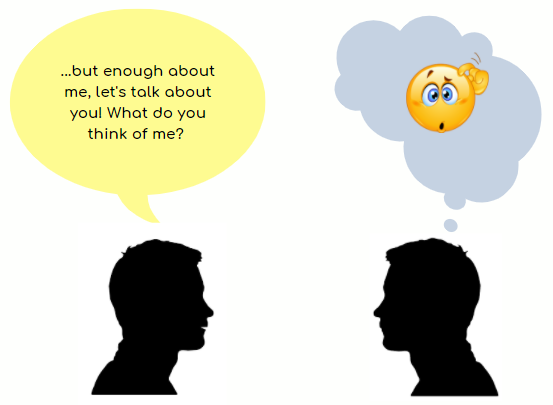

- We switch to the "Tell me about you!" tactic at the end of a conversation: by doing so, we give attention to the other person for a limited time. We display good manners while ignoring the speaker at the same time.

The support response:

- We keep the attention focused on the other person and on what they have to say;

- We offer reassurance that we are listening by not trying to monopolize the conversation. We allow the other person to continue speaking about themselves and their experience;

- We encourage the speaker to talk through invitation and inspiration.

Invitation: we make it clear that it is their turn to speak.

Inspiration: we say something that prompts the other person to

start or to continue talking;

- The support response relies on empathetic listening: trying to understand the other person's perspective rather looking at things (and judging) from our own point of view.

***

It must be noted that while the subjects of Dr. Derber’s investigation are American citizens, members of a highly competitive culture (an overview of the Anglo-American cluster can be found here), further research suggests that "individualistic promotion of self-focus over other-focus should be reflected in greater narcissism being expressed in people from more individualistic cultures” [note: participants from the United States reported more narcissism than participants from either Confucian/Southern Asia - or the Middle East].

On a related note, another study comparing narcissism and self-esteem in East and West Germany ("between 1949 and 1989/90, West Germany had an individualistic culture, whereas East Germany - at the time part of Eastern Europe - had a more collectivist culture”) states that "teaching children individualistic virtues may contribute to lower self-esteem”, for "individualistic societies promote achievement-dependent self-esteem, i.e., a self-esteem that is threatened by constant social comparisons and the necessity to achieve more than other individuals”.

Finally, with regard to communication and language, the same study concludes that "in modern Western societies the personal pronouns I and me are used more frequently than we and us”, findings that seem to validate Hofstede’s research on the cultural dimension known as collectivism/individualism: while in collectivist societies one’s identity and reputation is defined in terms of social roles ("I am a good son") and "I" is a not commonly used word, in individualistic societies self-concepts are based on personal traits rather than social roles ("I am kind" vs "I am a good son").

A good example of such differences in language can be found in the paper "Meaningfulness, the unsaid and translatability: Instead of an introduction” published by Open Linguistics, according to which:

"In English-speaking academia, authors are encouraged to be assertive and direct, to avoid distancing and other elusive discourse strategies and directly state their most important ideas. Contrariwise, in Japanese academic writing it is customary to be extremely polite and tentative in promoting one’s own ideas.”

***

For further reading material on the differences between the East and the West, please see the following articles:

- Giving and Losing Face: Honour, Social Reputation and Networking In Asian Countries

- I/II: Why Do We Work So Hard? Motivation and Reward Across Different Cultures

- II/II: Why Do We Work SO Hard? Introduction to Guilt- And Shame Cultures

- Social And Business Connections In China: An Insider’s Perspective On Guanxi

- Global Leadership And The Differences Between Indian and American Culture

SOURCES:

- Derber, C. (2000). "The pursuit of attention: Power and ego in everyday life”. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Foster, Joshua & Campbell, W. Keith & Twenge, Jean. (2003). "Individual differences in narcissism: Inflated self-views across the lifespan and around the world”. Journal of Research in Personality. 37. 469-486. 10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00026-6

- Hofstede, Geert H. (1997). "Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (second ed.)". New York: McGraw-Hill

- Keidan, A. (2015). "Meaningfulness, the unsaid and translatability: Instead of an introduction”. Open Linguistics, (1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2015-0023

- The Globe Project, Online: https://globeproject.com/

- Vater A, Moritz S, Roepke S (2018). "Does a narcissism epidemic exist in modern western societies? Comparing narcissism and self-esteem in East and West Germany”. PLoS ONE 13(1): e0188287.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188287