Overcoming The Challenges of Cross-Cultural Recruitment and Selection

In some of our previous articles on global leadership we’ve discussed about the meaning of “effective leadership” across cultures, about local preferences for certain traits ideal leaders should possess in order to be successful in their role: to continue the conversation, this week we’re going to talk about the “ideal candidate”, and the challenges of cross-cultural interviewing.

Why hiring for cultural fit is bad for diversity

We choose our favourite author as we do our friend, from a conformity of humour and disposition. Mirth or passion, sentiment or reflection; whichever of these most predominates in our temper, it gives us a peculiar sympathy with the writer who resembles us.”

- David Hume, Of the Standard of Taste -

Who is the “ideal candidate”, then, and what does being “a cultural fit” actually mean?

The Similarity-Attraction theory [1] suggests that we are naturally attracted to people who remind us of ourselves because they validate our own beliefs about ourselves while dissimilarity triggers negative feelings toward the other party (more on the topic at this link): this theory was also confirmed - among others - by a research conducted by Northwestern University management professor Lauren Rivera on the hiring process in elite professional service firms, according to which employers tend to seek candidates who are “not only competent but also culturally similar to themselves in terms of leisure pursuits, experiences, and self-presentation styles.”. Professor Ravera did also claim that “similarity is one of the most powerful drivers of attraction and evaluation in micro-social settings (Byrne 1971), including job interviews (Huffcutt 2011).” [2]

(Image source: Freepik)

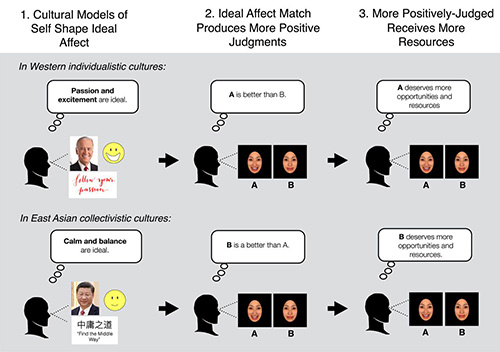

With regard to recruitment and selection practices in multicultural environment, it is extremely important to remember that adopting a one-size-fits-all approach and interviewing people in the same way regardless of their cultural background might not lead to the best possible outcomes: for instance, candidates from the majority of Western/individualistic societies - such as people from the Anglo-American or the Germanic Europe clusters - are likely to be used to a self-promotion style that emphasizes individual achievements and downplays shortcomings, while candidates from Eastern/collectivist cultures - such as people from the Confucian-Asia or the Southern Asia clusters, who value modesty, are likely to understate their accomplishments, perhaps by attributing them to favourable circumstances rather than personal merit. On a related note, the findings of a 2018 Stanford study (“Should job applicants be excited or calm? The role of culture and ideal affect in employment settings”) that compared European Americans and Asian Americans living in the United States with Chinese living in Hong Kong, suggested that people from different cultures have different ideas on how to make the “best impression” (note: such ideas are part of the deep culture realm/below the water line knowledge) at a job interview: “In Studies 1–2, European Americans wanted to convey High Arousal Positive states (HAP; excitement) more and Low Arousal Positive states (LAP; calm) less than did Hong Kong Chinese when applying for a job. European Americans also used more HAP words in their applications and showed more ‘high intensity’ smiles in their video introductions than did Hong Kong Chinese. In Study 3, European American working adults rated their ideal job applicant as being more HAP and less LAP than did Hong Kong Chinese, and in Study 4a, European American Masters of Business Administration (MBAs) were more likely to hire an excited (vs. calm) applicant for a hypothetical internship than were Hong Kong Chinese MBAs. Finally, in Study 4b, employees in a U.S. company were more likely to hire an excited (vs. calm) applicant for a hypothetical internship.” [3]

From the commentary “Why does passion matter more in individualistic cultures?” by Jeanne L. Tsai [4]:

An example of discrimination faced by applicants who belong to a minority group can be found in the study “Does Racial and Ethnic Discrimination Vary Across Minority Groups? Evidence from a Field Experiment” [5]: the researchers applied for entry level jobs using Anglo-Saxon, Indigenous, Italian, Chinese, and Middle Eastern names, and found “economically and statistically significant differences in callback rates, suggesting that ethnic minority candidates would need to apply for more jobs in order to receive the same number of interviews”.

In many scenarios where a standardized process to evaluate applicants has not been implemented and cultural assumptions are being made, hiring for cultural fit does therefore mean choosing the candidate the hiring manager best identifies with.

Differences to be aware of during cross-cultural interviews: some examples

“Come right out and say you want it: ‘It’s been great hearing you talk about the position. I’d love to work here, and I think I could do a terrific job for you’.”

- Kate White, I Shouldn't Be Telling You This: Success Secrets Every Gutsy Girl Should Know -

As highlighted in the previous section, people from different cultural backgrounds hold different beliefs about what constitutes the “right” or the “wrong” way to handle a specific situation.

Asian nationals, for example, come in most cases from high-context, collectivist, high power distance, conservative cultures: since decision-making processes do usually involve the whole group, knowledge of background information tends to be assumed. Asian applicants do therefore keep their answers to the interviewer simple and modest, are (to some extent) accepting of personal questions, they maintain a formal, respectful, and composed behaviour throughout the interview. Candidates from English speaking countries, on the other hand, come from low-context, individualistic, low power distance cultures that emphasize the importance of independence and place great value on personal accomplishments: their communication style is relaxed and informal, they’re mindful of time (in monochronic cultures, “time is money”), they might perceive personal questions as inappropriate in a business context, they’re likely to talk enthusiastically about their own skills, background, and achievements.

With regard to body language and non-verbal communication, it is important to remember that gestures carry different meanings in different countries (for example, maintaining eye contact is considered rude in the majority of Asian countries and in the Middle East, while in most Western countries it’s a sign of respect, attention, and self-confidence).

(Image source: Freepik)

A word of advice

“But I think that no matter how smart, people usually see what they're already looking for, that's all.”

- Veronica Roth, Allegiant -

Recruiting across cultures isn’t an easy task. While it’s not possible to recommend a universal approach to an infinite number of potential scenarios, the following suggestions will help make the interview process easier and fairer for candidates from different backgrounds:

ensure that all the recruiters involved in the selection and hiring process are familiar with the concepts of implicit bias (the unconscious preference or aversion towards a specific group of people. Implicit bias tests can be taken here, https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/selectatest.html), and aware of the fact that such bias might affect their judgement;

ensure that all the recruiters involved in the selection and hiring process are prepared to dealing with cultural differences, that they have done some research on the candidates’ background and acknowledged the fact that the might have to switch to a different communication style in order to build rapport;

avoid using jargon, and be mindful of the fact that someone who’s first language isn’t English might need more time to reflect on a question and make their point;

if possible, provide candidates with the opportunity to be interviewed by someone of the same culture, and/or ensure that all the recruiters involved in the selection and hiring process consult with a member of the target group to get some guidance prior to the interview.

Sources

[1] Byrne, D. (1971). “The attraction paradigm”. New York: Academic Press

[2] Rivera LA. “Hiring as Cultural Matching: The Case of Elite Professional Service Firms”. American Sociological Review. 2012;77(6):999-1022. doi:10.1177/0003122412463213

[3] Bencharit LZ, Ho YW, Fung HH, Yeung DY, Stephens NM, Romero-Canyas R, Tsai JL. “Should job applicants be excited or calm? The role of culture and ideal affect in employment settings”. Emotion. 2019 Apr;19(3):377-401. doi: 10.1037/emo0000444. Epub 2018 Jul 5. PMID: 29975076.

Tsai, Jeanne. (2021). “Why does passion matter more in individualistic cultures?”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118. e2102055118. 10.1073/pnas.2102055118.

Booth, Alison & Leigh, Andrew & Varganova, Elena. (2009). “Does Racial and Ethnic Discrimination Vary Across Minority Groups? Evidence from a Field Experiment”. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.1521229.

Further recommended readings:

- Personal Values and Intended Self‐Presentation during Job Interviews: A Cross‐Cultural Comparison (Bye, Hege & Sandal, Gro & Van de Vijver, Fons & Sam, David & Çakar, Nigar & Franke, Gabriele. (2011). Personal Values and Intended Self‐Presentation during Job Interviews: A Cross‐Cultural Comparison. Applied Psychology. 60. 160 - 182. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2010.00432.x)

- Intended Self-Presentation Tactics in Job Interviews: A 10-Country Study (Sandal, Gro & Van de Vijver, Fons & Bye, Hege & Sam, David & Amponsah, Benjamin & Çakar, Nigar & Franke, Gabriele & Ismail, Rosnah & Kjellsen, Kristine & Kosic, Ankica & Leontieva, Anna & Mortazavi, Shahrnaz & Sun, Catherine. (2014). Intended Self-Presentation Tactics in Job Interviews: A 10-Country Study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 10.1177/0022022114532353)